horothesia

thoughts and comments across the boundaries of computing, ancient history, epigraphy and geography ... oh, and barbeque, coffee and rockets

SyntaxHighlighter

Sunday, April 8, 2018

So long, Blogger

Well, Horothesia has had a good decade+ here at blogger, but I feel it's time for a change. I've copied the entire archive to my new site and blog at paregorios.org and it's there that I'll post any new blog content.

Labels:

meta

Friday, February 2, 2018

Preserving Accented and Non-Roman Characters in CSV Workflows

Digital work in and around the Humanities often involves moving data from one system or format to another. That data often involves complex textual materials in multiple languages and writing systems. One commonly used format is the "Comma-Separated Values" text file. It's not uncommon to find that characters not used in English get garbled when exported from a spreadsheet program like Microsoft Excel to CSV (or imported from CSV into such a program). What's going on and how do you make it stop?

Why

CSV began life in an era before Unicode and, because of that background, some software assumes that CSV should be encoding using the ASCII text encoding scheme (some older versions of Excel). Some software defaults to using ASCII, but you can override it manually (more recent versions of Excel). Some software tries to guess what encoding to use when reading or writing a given CSV file, but how it guesses may not be foolproof. Some software writes a special code called a Byte-Order Mark (BOM) into the beginning of any CSV file that uses a Unicode-aware encoding (Excel for Mac 2016). Some software doesn't expect a BOM and will fail to read the data correctly even if the encoding (e.g., UTF-8) is otherwise supported.How to make it stop

The best way to make it stop is to:- Make sure that any CSV file you import or export is encoded in UTF-8 without a Byte-Order Mark.

- Make sure that any software you're using is capable of reading and writing CSV files in UTF-8 without BOM and has been told to do so.

Friday, October 13, 2017

Using OpenRefine with Pleiades

This past summer, DC3's Ryan Baumann developed a reconciliation service for Pleiades. He's named it Geocollider. It has two manifestations:

1. Create a new column containing Pleiades JSON.

2. Create another new column by parsing the representative longitude out of the JSON.

From the drop-down menu on the column containing JSON, select "Edit column" -> "Add column based on this column..."

3. Create a column for the latitude

4. Carry on ...

- Upload a CSV file containing placenames and/or longitude/latitude coordinates, set matching parameters, and get back a CSV file of possible matches.

- An online Application Programming Interface (API) compatible with the OpenRefine data-cleaning tool.

The first version is relatively self-documenting. This blog post is about using the second version with OpenRefine.

Reconciliation

I.e., matching (collating, aligning) your placenames against places in Pleiades.

Running OpenRefine against Geocollider for reconciliation purposes is as easy as:

- Download and install OpenRefine.

- Follow the standard OpenRefine instructions for "Reconciliation," but instead of picking the pre-installed "Wikidata Reconciliation Service," select the "Add standard service..." button and enter "http://geocollider-sinatra.herokuapp.com/reconcile" in the service URL dialog, then select the "Add Service" button.

When you've worked through the results of your reconciliation process and selected matches, OpenRefine will have added the corresponding Pleiades place URIs to your dataset. That may be all you want or need (for example, if you're preparing to bring your own dataset into the Pelagios network) ... just export the results and go on with your work.

But if you'd like to actually get information about the Pleiades places, proceed to the next section.

Augmentation

I.e., pulling data from Pleiades into OpenRefine and selectively parsing it for information to add to your dataset.

Pleiades provides an API for retrieving information about each place resource it contains. One of the data formats this API provides is JSON, which is a format with which OpenRefine is designed to work. The following recipe demonstrates how to use the General Refine Expression Language to extract the "Representative Location" associated with each Pleiades place.

Caveat: this recipe will not, at present, work with the current Mac OSX release of OpenRefine (2.7), even though it should and hopefully eventually will. It has not been tested with the current releases for Windows and Linux, but they probably suffer from the same limitations as the OSX release. More information, including a non-trivial technical workaround, may be had from OpenRefine Issue 1265. I will update this blog post if and when a resolution is forthcoming.

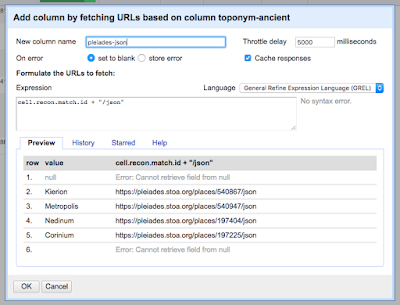

Assuming your dataset is open in an OpenRefine project and that it contains a column that has been reconciled using Geocollider, select the drop-down menu on that column and choose "Edit column" -> "Add column by fetching URLs ..."

In the dialog box, provide a name for the new column you are about to create. In the "expression" box, enter a GREL expression that retrieves the Pleiades URL from the reconciliation match on each cell and appends the string "/json" to it:

cell.recon.match.id + "/json"

OpenRefine retrieves the JSON for each matched place from Pleiades and inserts it into the appropriate cell in the new column.

2. Create another new column by parsing the representative longitude out of the JSON.

From the drop-down menu on the column containing JSON, select "Edit column" -> "Add column based on this column..."

In the dialog box, provide a name for the new column. In the expression box, enter a GREL expression that extracts the longitude from the reprPoint object in the JSON:

value.parseJson()['reprPoint'][0]

Note that the reprPoint object contains a two-element list, like:

[ 37.328382, 38.240638 ]

Pleiades follows the GeoJSON specification in using the longitude, latitude ordering of elements in coordinate pairs so, to get the longitude, you use the index (0) for the first element in the list.

Use the method explained in step 2, but select the second list item from reprPoint (index=1).

Your data set in OpenRefine will now look something like this:

Tuesday, January 31, 2017

Scheduled Votes on Bills in Congress, Week of 30 January 2017

I'll try to make these better in future (e.g., with actionable links and headers and such), but right now I figured it was best to paste as plaintext in order to avoid a bunch of interstitial tracking links that IFTTT and gmail inserted.

H.R. 347 - DHS Acquisition Documentation Integrity Act of 2017

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 347 - DHS Acquisition Documentation Integrity Act of 2017

Sponsor

Rep. Bonnie Watson Coleman

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 560 - To amend the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area Improvement Act to provide access to certain vehicles serving residents of municipalities adjacent to the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, and for other purposes.

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 560 - To amend the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area Improvement Act to provide access to certain vehicles serving residents of municipalities adjacent to the Delaware Water Gap National Recreation Area, and for other purposes.

Sponsor

Rep. Tom Marino

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 58 - First Responder Identification of Emergency Needs in Disaster Situations

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 58 - First Responder Identification of Emergency Needs in Disaster Situations

Sponsor

Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 276 - A bill to amend title 49, United States Code, to ensure reliable air service in American Samoa.

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 276 - A bill to amend title 49, United States Code, to ensure reliable air service in American Samoa.

Sponsor

Del. Aumua Amata

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 366 - DHS SAVE Act

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 366 - DHS SAVE Act

Sponsor

Rep. Scott Perry

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 437 - Medical Preparedness Allowable Use Act

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 437 - Medical Preparedness Allowable Use Act

Sponsor

Rep. Gus Bilirakis

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 505 - Border Security Technology Accountability Act of 2017

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 505 - Border Security Technology Accountability Act of 2017

Sponsor

Rep. Martha McSally

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 526 - Counterterrorism Advisory Board Act of 2017

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 526 - Counterterrorism Advisory Board Act of 2017

Sponsor

Rep. John Katko

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 549 - Transit Security Grant Program Flexibility Act

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 549 - Transit Security Grant Program Flexibility Act

Sponsor

Rep. Daniel Donovan

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 584 - Cyber Preparedness Act of 2017

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 584 - Cyber Preparedness Act of 2017

Sponsor

Rep. Daniel Donovan

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 612 - United States-Israel Cybersecurity Cooperation Enhancement Act of 2017

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 612 - United States-Israel Cybersecurity Cooperation Enhancement Act of 2017

Sponsor

Rep. Jim Langevin

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 642 - To amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to enhance the partnership between the Department of Homeland Security and the National Network of Fusion Centers, and for other purposes.

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 642 - To amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to enhance the partnership between the Department of Homeland Security and the National Network of Fusion Centers, and for other purposes.

Sponsor

Rep. Lou Barletta

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 655 - To amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to establish the Securing the Cities program to enhance the ability of the United States to detect and prevent terrorist attacks and other high consequence events utilizing nuclear or other rad...

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 655 - To amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to establish the Securing the Cities program to enhance the ability of the United States to detect and prevent terrorist attacks and other high consequence events utilizing nuclear or other radiological materials that pose a high risk to homeland security in high-risk urban areas, and for other purposes.

Sponsor

Rep. Daniel Donovan

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 665 - To modernize and enhance airport perimeter and access control security by requiring updated risk assessments and the development of security strategies, and for other purposes.

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 665 - To modernize and enhance airport perimeter and access control security by requiring updated risk assessments and the development of security strategies, and for other purposes.

Sponsor

Rep. William Keating

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 666 - To amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to establish the Insider Threat Program, and for other purposes.

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 666 - To amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to establish the Insider Threat Program, and for other purposes.

Sponsor

Rep. Pete King

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 677 - To amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to establish chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear intelligence and information sharing functions of the Office of Intelligence and Analysis of the Department of Homeland Security and...

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 677 - To amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to establish chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear intelligence and information sharing functions of the Office of Intelligence and Analysis of the Department of Homeland Security and to require dissemination of information analyzed by the Department to entities with responsibilities relating to homeland security, and for other purposes.

Sponsor

Rep. Martha McSally

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 678 - To require an assessment of fusion center personnel needs, and for other purposes.

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 678 - To require an assessment of fusion center personnel needs, and for other purposes.

Sponsor

Rep. Martha McSally

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 687 - To amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to establish a process to review applications for certain grants to purchase equipment or systems that do not meet or exceed any applicable national voluntary consensus standards, and for other...

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 687 - To amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to establish a process to review applications for certain grants to purchase equipment or systems that do not meet or exceed any applicable national voluntary consensus standards, and for other purposes.

Sponsor

Rep. Donald Payne

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 690 - To amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to enhance certain duties of the Domestic Nuclear Detection Office, and for other purposes.

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 690 - To amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to enhance certain duties of the Domestic Nuclear Detection Office, and for other purposes.

Sponsor

Rep. Cedric Richmond

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

H.R. 697 - To amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to improve the management and administration of the security clearance processes throughout the Department of Homeland Security, and for other purposes.

The House of Representatives is scheduled to vote the week of January 30th, 2017 on H.R. 697 - To amend the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to improve the management and administration of the security clearance processes throughout the Department of Homeland Security, and for other purposes.

Sponsor

Rep. Bennie Thompson

via Sunlight Foundation http://ift.tt/2jJ4Mmz For more information on a bill or resolution: http://ift.tt/1c1EyNR To contact your Representative: http://ift.tt/P3cvWa To contact your Senator: http://ift.tt/y4GfE9 January 30, 2017 at 05:13AM

via ProPublica http://docs.house.gov/floor/Default.aspx?date=2017-01-30

Labels:

resist

Monday, January 30, 2017

On Hidden Figures

This weekend I finally got a chance to see Hidden Figures. The large theater was two-thirds full or so, mostly white (as one might expect in South Huntsville), mostly women and girls (you missed out, dudes, it was great).

There was a profound mix of audience laughter and silence throughout. At the end of the historical/photographic epilogue, there was a moment of silence into which a female voice clearly whispered: "That was amazing!" Then LOUD APPLAUSE.

That's the world I thought I was living in. I want it back. For real.

Let's go get it.

Thursday, January 26, 2017

Paying for the wall

It's my opinion that the Trump team never imagined that Mexico would "pay for the wall." What's always been meant is "I will make those Mexicans pay for the wall. I will make them pay."

So, the plan is surely trade sanctions and more. The real point of the whole thing will never be cost recovery (nor true border security). It's ritualized combat display: the leader publicly acting out his supposed manly vigor and strength of will by exercising the organs of state symbolically to humiliate, impoverish, emasculate, feminize, and punish a straw-man external enemy erected for the purpose. He will try to supplant the reality of the Mexican people's complex humanity, society, and shared-with-us economy with a fictionally puny, dirty, criminal, and base caricature. He will ostentatiously pummel that piñata in order to give the masses of his supporters a vicarious victory and a sham sense of security, a warm spatter of fake enemy blood, while his regime, less watched, loots our inheritance and undermines our liberties, doubling down on the very sorts of injustices that underlie the rage against government and establishment that helped put him in office in the first place.

So, the plan is surely trade sanctions and more. The real point of the whole thing will never be cost recovery (nor true border security). It's ritualized combat display: the leader publicly acting out his supposed manly vigor and strength of will by exercising the organs of state symbolically to humiliate, impoverish, emasculate, feminize, and punish a straw-man external enemy erected for the purpose. He will try to supplant the reality of the Mexican people's complex humanity, society, and shared-with-us economy with a fictionally puny, dirty, criminal, and base caricature. He will ostentatiously pummel that piñata in order to give the masses of his supporters a vicarious victory and a sham sense of security, a warm spatter of fake enemy blood, while his regime, less watched, loots our inheritance and undermines our liberties, doubling down on the very sorts of injustices that underlie the rage against government and establishment that helped put him in office in the first place.

Labels:

resist

Saturday, April 9, 2016

Stable Orbits or Clear Air Turbulence: Capacity, Scale, and Use Cases in Geospatial Antiquity

I delivered the following talk on 8 April 2016 at the Mapping the Past: GIS Approaches to Ancient History conference at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Update (19 April 2016): video is now available on YouTube, courtesy of the Ancient World Mapping Center.

How many of you are familiar with Jo Guldi's on-line essay on the "Spatial Turn" in western scholarship? I highly recommend it. It was published in 2011 as a framing narrative for the Spatial Humanities website, a publication of the Scholar's Lab at the University of Virginia. The website was intended partly to serve as a record of the NEH-funded Institute for Enabling Geospatial Scholarship. That Institute, organized in a series of three thematic sessions, was hosted by the Scholars Lab in 2009 and 2010. The essay begins as follows:

“Landscape turns” and “spatial turns” are referred to throughout the academic disciplines, often with reference to GIS and the neogeography revolution ... By “turning” we propose a backwards glance at the reasons why travelers from so many disciplines came to be here, fixated upon landscape, together. For the broader questions of landscape – worldview, palimpsest, the commons and community, panopticism and territoriality — are older than GIS, their stories rooted in the foundations of the modern disciplines. These terms have their origin in a historic conversation about land use and agency.Professor Guldi's essay takes us on a tour through the halls of the Academy, making stops in a variety of departments, including Anthropology, Literature, Sociology, and History. She traces the intellectual innovations and responses -- prompted in no small part by the study and critique of the modern nation state -- that iteratively gave rise to many of the research questions and methods that concern us at this conference. I don't think it would be a stretch to say that not only this conference but its direct antecedents and siblings -- the Ancient World Mapping Center and its projects, the Barrington Atlas and its inheritors -- are all symptoms of the spatial turn.

So what's the point of my talk this evening? Frankly, I want to ask: to what degree do we know what we're doing? I mean, for example, is spatial practice a subfield? Is it a methodology? It clearly spans chairs in the Academy. But does it answer -- better or uniquely? -- a particular kind of research question? Is spatial inquiry a standard competency in the humanities, or should it remain the domain of specialists? Does it inform or demand a specialized pedagogy? Within ancient studies in particular, have we placed spatially informed scholarship into a stable orbit that we can describe and maintain, or are we still bumping and bouncing around in an unruly atmosphere, trying to decide whether and where to land?

Some will recognize in this framework questions -- or should we say anxieties -- that are also very much alive for the digital humanities. The two domains are not disjoint. Spatial analysis and visualization are core DH activities. The fact that the Scholar's Lab proposed and the NEH Office of Digital Humanities funded the Geospatial Institute I mentioned earlier underscore this point.

So, when it comes to spatial analysis and visualization, what are our primary objects of interest? "Location" has to be listed as number one, right? Location, and relative location, are important because they are variables in almost every equation we could care about. Humans are physical beings, and almost all of our technology and interaction -- even in the digital age -- are both enabled and constrained by physical factors that vary not only in time, but also in three-dimensional space. If we can locate people, places, and things in space -- absolutely or relatively -- then we can open our spatial toolkit. Our opportunities to explore become even richer when we can access the way ancient people located themselves, each other, places, and things in space: the rhetoric and language they used to describe and depict those locations.

The connections between places and between places and other things are also important. The related things can be of any imaginable type: objects, dates, events, people, themes. We can express and investigate these relationships with a variety of spatial and non-spatial information structures: directed graphs and networks for example. There are digital tools and methods at our disposal for working with these mental constructs too, and we'll touch on a couple of examples in a minute. But I'd like the research questions, rather than the methods, to lead the discussion.

When looking at both built and exploited natural landscapes, we are often interested in the functions humans impart to space and place. These observations apply not only to physical environments, but also to their descriptions in literature and their depictions in art and cartography. And so spatial function is also about spatial rhetoric, performance, audience, and reception.

Allow me a brief example: the sanctuary of Artemis Limnatis at Volimnos in the Tayegetos mountains (cf. Koursoumis 2014; Elliott 2004, 74-79 no. 10). Its location is demonstrated today only by scattered architectural, artistic, and epigraphic remains, but epigraphic and literary testimony make it clear that it was just one of several such sanctuaries that operated at various periods and places in the Peloponnese. Was this ancient place of worship located in a beautiful spot, evocative of the divine? Surely it was! But it -- and its homonymous siblings -- also existed to claim, mark, guard, consecrate, and celebrate political and economic assertions about the land it overlooked. Consequently, the sanctuary was a locus of civic pride for the Messenians and the Spartans, such that -- from legendary times down to at least the reign of Vespasian -- it occasioned both bloodshed and elite competition for the favor of imperial powers. Given the goddess's epithet (she is Artemis Of The Borders), the sanctuary's location, and its history of contentiousness, I don't think we're surprised that a writer like Tacitus should take notice of delegations from both sides arriving in Rome to argue for and against the most recent outcome in the struggle for control of the sanctuary. I can't help but imagine him smirking as he drops it into the text of his Annals (4.43), entirely in indirect discourse and deliberately ambiguous of course about whether the delegations appeared before the emperor or the Senate. It must have given him a grim sort of satisfaction to be able to record a notable interaction between Greece and Rome during the reign of Tiberius that also served as a metaphor for the estrangement of emperor and senate, of new power and old prerogatives.

Epigraphic and literary analysis can give us insight into issues of spatial function, and so can computational methods. The two approaches are complementary, sometimes informing, supporting, and extending each other, other times filling in gaps the other method leaves open. Let's spend some time looking more closely at the computational aspects of spatial scholarship.

A couple of weeks ago, I got to spend some time talking to Lisa Mignone at Brown about her innovative work on the visibility of temples at Rome with respect to the valley of the Tiber and the approaches to the city. Can anyone doubt that, among the factors at play in the ancient siting and subsequent experience of such major structures, there's a visual expression of power and control at work? Mutatis mutandis, you can feel something like it today if you get the chance to walk the Tiber at length. Or, even if you just go out and contemplate the sight lines to the monuments and buildings of McCorkle Place here on the UNC campus. To be sure, in any such analysis there is a major role for the mind of the researcher ... in interpretation, evaluation, narration, and argument, and that researcher will need to be informed as much as possible by the history, archaeology, and literature of the place. But, depending on scale and the alterations that a landscape has undergone over time, there is also the essential place of viewshed analysis. Viewsheds are determined by assessing the visibility of every point in an area from a particular point of interest. Can I see the University arboretum from the north-facing windows of the Ancient World Mapping Center on the 5th floor of Davis Library? Yes, the arboretum is in the Center's viewshed. Well, certain parts of it anyway. Can I see the Pit from there? No. Mercifully, the Pit is not in the Center's viewshed.

In one methodological respect, Professor Mignone's work is not new. Viewshed analysis has been widely used for years in archaeological and historical study, at levels ranging from the house to the public square to the civic territory and beyond. I doubt anyone could enumerate all the published studies without a massive amount of bibliographical work. Perhaps the most well known -- if you'll permit an excursion outside the domain of ancient studies -- is Anne Kelly Knowles' work (with multiple collaborators) on the Battle of Gettysburg. What could the commanders see and when could they see it? There's a fascinating, interactive treatment of the data and its implications published on the website of Smithsonian Magazine.

Off the top of my head, I can point to a couple of other examples in ancient studies. Though their mention will only scratch the surface of the full body of work, I think they are both useful examples. There's Andrew Sherrat's 2004 treatment of Myceneae, which explores the site's visual and topographical advantages in an accessible, online form. It makes use of cartographic illustration and accessible text to make its points about strategically and economically interesting features of the site.

I also recall a poster by James Newhard and several collaborators that was presented at the 2012 meeting of the Archaeological Institute of America. It reported on the use of viewshed analysis and other methods as part of an integrated approach to identifying Byzantine defensive systems in North Central Anatolia. The idea here was that the presence of a certain kind of viewshed -- one offering an advantage for surveillance of strategically useful landscape elements like passes and valleys -- might lend credance to the identification of ambiguous archaeological remains as fortifications. Viewshed analysis is not just revelatory, but can also be used for predictive and taxonomic tasks.

In our very own conference, we'll hear from Morgan Di Rodi and Maria Kopsachelli about their use of viewshed analysis and other techniques to refine understanding of multiple archaeological sites in northwest Greece. So we'll get to see viewsheds in action!

Like most forms of computational spatial analysis, viewshed work is most rigorously and uniformly accomplished with GIS software, supplied with appropriately scaled location and elevation data. To do it reliably by hand for most interesting cases would be impossible. These dependencies on software and data, and the know-how to use them effectively, should draw our attention to some important facts. First of all, assembling the prerequisites of non-trivial spatial analysis is challenging and time consuming. More than once, I've heard Prof. Knowles say that something like ninety percent of the time and effort in a historical GIS project goes into data collection and preparation. Just as we depend on the labor of librarians, editors, philologists, Renaissance humanists, medieval copyists, and their allies for our ability to leverage the ancient literary tradition for scholarly work, so too we depend on the labor of mathematicians, geographers, programmers, surveyors, and their allies for the data and computational artifice we need to conduct viewshed analysis. This inescapable debt -- or, if you prefer, this vast interdisciplinary investment in our work -- is a topic to which I'd like to return at the end of the talk.

Before we turn our gaze to other methods, I'd like to talk briefly about other kinds of sheds. Watershed analysis -- the business of calculating the entire area drained and supplied by a particular water system -- is a well established method of physical geography and the inspiration for the name viewshed. It has value for cultural, economic, and historical study too, and so should remain on our spatial RADAR. In fact, Melissa Huber's talk on the Roman water infrastructure under Claudius will showcase this very method.

Among Sarah Bond's current research ideas is a "smells" map of ancient Rome. Where in the streets of ancient Rome would you have encountered the odors of a bakery or a latrine a fullonica. And -- God help you -- what would it have smelled like? Will it be possible at some point to integrate airflow and prevailing wind models with urban topography and location data to calculate "smellsheds" or "nosescapes" for particular installations and industries? I sure hope so! Sound sheds ought to be another interesting possibility; we ought to look for leadership to the work of people like Jeff Veitch who is investigating acoustics and architecture at Ostia, and the Virtual Paul's Cross project at North Carolina State.

Every bit as interesting as what the ancients could see, and from where they could see it, is the question of how they saw things in space and how they described them. Our curiosity about ancient geographic mental models and worldview drives us to ask questions like ones Richard Talbert has been asking: did the people living in a Roman province think of themselves as "of the province" in the way modern Americans think of themselves as being North Carolinians or Michiganders? Were the Roman provinces strictly administrative in nature, or did they contribute to personal or corporate identity in some way? Though not a field that has to be plowed only with computers, questions of ancient worldview do sometimes yield to computational approaches.

Consider, for example, the work of Elton Barker and colleagues under the rubric of the Hestia project. Here's how they describe it:

Using a digital text of Herodotus’s Histories, Hestia uses web-mapping technologies such as GIS, Google Earth and the Narrative TimeMap to investigate the cultural geography of the ancient world through the eyes of one of its first witnesses.In Hestia, word collocation -- a mainstay of computational text analysis -- is brought together and integrated with location-based measures to interrogate not only the spatial proximity of places mentioned by Herodotus, but also the textual proximities of those place references. With these keys, the Hestia team opens the door to Herodotus' geomind and that of the culture he lived in: what combinations of actual location, historical events, cultural assumptions, and literary agenda shape the mention of places in his narrative?

Hestia is not alone in exploring this particular frontier. Tomorrow we'll hear from Ryan Horne about his collaborative work on the Big Ancient Mediterranean project. Among its pioneering aspects is the incorporation of data about more than the collocation of placenames in primary sources and the relationships of the referenced places with each other. BAM also scrutinizes personal names and the historical persons to whom they refer. Who is mentioned with whom where? What can we learn from exploring the networks of connection that radiate from such intersections?

The introduction of a temporal axis into geospatial calcuation and visualization is also usually necessary and instructive in spatial ancient studies, even if it still proves to be more challenging in standard GIS software than one might like. Amanda Coles has taken on that challenge, and will be telling us more about what it's helped her learn about the interplay between warfare, colonial foundations, road building, and the Roman elites during the Republic.

Viewsheds, worldviews, and temporality, oh my!

How about spatial economies? How close were sources of production to their markets? How close in terms of distance? How close in terms of travel time? How close in terms of cost to move goods?

Maybe we are interested in urban logistics. How quickly could you empty the colosseum? How much bread could you distribute to how many people in a particular amount of time at a particular place? What were the constraints and capacities for transport of the raw materials? What do the answers to such questions reveal about the practicality, ubiquity, purpose, social reach, and costs of communal activities in the public space? How do these conclusions compare with the experiences and critiques voiced in ancient sources?

How long would it take a legion to move from one place to another in a particular landscape? What happens when we compare the effects of landscape on travel time with the built architecture of the limes or the information we can glean about unit deployment patterns from military documents like the Vindolanda tablets or the ostraca from Bu Njem?

The computational methods involved in these sorts of investigations have wonderful names, and like the others we've discussed, require spatial algorithms realized in specialized software. Consider cost surfaces: for a particular unit of area on the ground, what is the cost in time or effort to pass through it? Consider network cost models: for specific paths between nodal points, what is the cost of transit? Consider least cost path analysis: given a cost surface or network model, what is the cheapest path available between two points?

Many classicists will have used Orbis: The Stanford Geospatial Network Model of the Roman World. The Orbis team, assembled by Walter Scheidel, has produced an online environment in which one can query a network model of travel costs between key nodal points in the Roman world, varying such parameters as time of year and mode of transport. This model, and its digital modes of access, bring us to another vantage point. How close were two places in the Roman world, not as the crow flies, not in terms of miles along the road, but as the boat sailed or the feet walked.

Barbora Weissova is going to talk to us tomorrow about her work in and around Nicaea. Among her results, she will discuss another application of Least Cost Path Analysis: predicting the most likely route for a lost ancient roadway.

It's not just about travel, transport, and cost. Distribution patterns are of interest too, often combined with ceramic analysis, or various forms of isotopic or metallurgical testing, to assess the origin, dissemination, and implications of ancient objects found in the landscape. Inscriptions, coins, portable antiquities, architectural and artistic styles, pottery, all have been used in such studies. Corey Ellithorpe is going to give us a taste of this approach in numismatics by unpacking the relationship between Roman imperial ideology and regional distribution patterns of coins.

I'd like to pause here for just a moment and express my hope that you'll agree with the following assessment. I think we are in for an intellectual feast tomorrow. I think we should congratulate the organizers of the conference for such an interesting, and representative, array of papers and presentations. That there is on offer such a tempting smorgasbord is also, of course, all to the credit of the presenters and their collaborators. And surely it must be a factor as we consider the ubiquity and disciplinarity of spatial applications in ancient studies.

Assiduous students of the conference program will notice that I have neglected yet to mention a couple of the papers. Fear not, for they feature in the next section of my talk, which is -- to borrow a phrase from Meghan Trainor and Kevin Kadish -- all about that data.

So, conference presenters, would you agree with the dictum I've attributed to Anne Knowles? Does data collection and preparation take up a huge chunk of your time?

Spatial data, particularly spatial data for ancient studies, doesn't normally grow on trees, come in a jar, or sit on a shelf. The ingredients have to be gathered and cleaned, combined and cooked. And then you have to take care of it, transport it, keep track of it, and refashion it to fit your software and your questions. Sometimes you have to start over, hunt down additional ingredients, or try a new recipe. This sort of iterative work -- the cyclic remaking of the experimental apparatus and materials -- is absolutely fundamental to spatially informed research in ancient studies.

If you were hoping I'd grind an axe somewhere in this talk, you're in luck. It's axe grinding time.

There is absolutely no question in my mind that the collection and curation of data is part and parcel of research. It is a research activity. It has research outcomes. You can't answer questions without it. If you aren't surfacing your work on data curation in your CV, or if you're discounting someone else's work on data curation in decisions about hiring, tenure, and promotion, then I've got an old Bob Dylan song I'd like to play for you.

- Archive and publish your datasets.

- Treat them as publications in your CV.

- Write a review of someone else's published dataset and try to get it published.

- Document your data curation process in articles and conference presentations.

Right. Axes down.

So, where does our data come from? Sometimes we can get some of it in prepared form, even if subsequent selection and reformatting is required. For some areas and scales, modern topography and elevation can be had in various raster and vector formats. Some specialized datasets exist that can be used as a springboard for some tasks. It's here that the Pleiades project, which I direct, seeks to contribute. By digitizing not the maps from the Barrington Atlas, but the places and placenames referenced on those maps and in the map-by-map directory, we created a digital dataset with potential for wide reuse. By wrapping it in a software framework that facilitates display, basic cartographic visualization, and collaborative updates, we broke out of the constraints of scale and cartographic economy imposed by the paper atlas format. Pleiades now knows many more places than the Barrington did, most of these outside the cultures with which the Atlas was concerned. More precise coordinates are coming in too, as are more placename variants and bibliography. All of this data is built for reuse. You can collect it piece by piece from the web interface or download it in a number of formats. You can even write programs to talk directly to Pleiades for you, requesting and receiving data in a computationally actionable form. The AWMC has data for reuse too, including historical coastlines and rivers and map base materials. It's all downloadable in GIS-friendly formats.

But Pleiades and the AWMC only help for some things. It's telling that only a couple of the projects represented at this conference made use of Pleiades data. That's not because Pleiades is bad or because the authors didn't know about Pleiades or the Center. It's because the questions they're asking require data that Pleiades is not designed to provide.

It's proof of the point I'd like to underline: usually -- because your research question is unique in some way, otherwise you wouldn't be pursuing it -- you're going to have to get your hands dirty with data collection.

But before we get dirty, I'm obliged to point out that, although Pleiades has received significant, periodic support from the National Endowment for the Humanities since 2006, the views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this lecture do not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

We've already touched on the presence of spatial language in literature. For some studies, the placenames, placeful descriptions, and narratives of space found in both primary and secondary sources constitute raw data we'd like to use. Identifying and extracting such data is usually a non-trivial task, and may involve a combination of manual and computational techniques, the latter depending on the size and tractability of the textual corpus in question and drawing on established methods in natural language processing and named entity recognition. It's here we may encounter "geoparsing" as a term of art. Many digital textual projects and collections are doing geoparsing: individual epigraphic and papyrological publications using the Text Encoding Initiative and EpiDoc Guidelines; the Perseus Digital Library; the Pelagios Commons by way of its Recogito platform. The China Historical GIS is built up entirely from textual sources, tracking each placename and each assertion of administrative hierarchy back to its testimony.

For your project, you may be able to find geoparsed digital texts that serve your needs, or you may need to do the work yourself. Either way, some transformation on the results of geoparsing is likely to be necessary to make them useful in the context of your research question and associated apparatus.

Relevant here is Micah Myers's conference paper. He is going to bring together for us the analysis and visualization of travel as narrated in literature. I gather from his abstract that he'll show us not only a case study of the process, but discuss the inner workings of the on-line publication that has been developed to disseminate the work.

Geophysical and archaeological survey may supply your needs. Perhaps you'll have to do fieldwork yourself, or perhaps you can collect the information you need from prior publications or get access to archival records and excavation databases. Maybe you'll get lucky and find a dataset that's been published into OpenContext, the British Archaeology Data Service, or tDAR: the Digital Archaeological Record. But using this data requires constant vigilance, especially when it was collected for some purpose other than you own. What were the sampling criteria? What sorts of material were intentionally ignored? What circumstances attended collection and post-processing?

Sometimes the location data we need comes not from a single survey or excavation, but from a large number of possibly heterogeneous sources. This will be the case for many spatial studies that involve small finds, inscriptions, coins, and the like. Fortunately, many of the major documentary, numismatic, and archaeological databases are working toward the inclusion of uniform geographic information in their database records. This development, which exploits the unique identifying numbers that Pleiades bestows on each ancient place, was first championed by Leif Isaksen, Elton Barker, and Rainer Simon of the Pelagios Commons project. If you get data from a project like the Heidelberg Epigraphic Databank, papyri.info, the Arachne database of the German Archaeological Institute, the Online Coins of the Roman Empire, or the Perseus Digital Library, you can count on being able to join it easily with Pleiades data and that of other Pelagios partners. Hopefully this will save some of us some time in days to come.

Sometimes what's important from a prior survey will come to us primarily through maps and plans. Historical maps may also carry information we'd like to extract and interpret. There's a whole raft of techniques associated with the scanning, georegistration, and georectification (or warping) of maps so that they can be layered and subjected to feature tracing (or extraction) in GIS software. Some historic cartofacts -- one thinks of the Peutinger map and medieval mappae mundi as examples -- are so out of step with our expectations of cartesian uniformity that these techniques don't work. Recourse in such cases may be had to first digitizing features of interest in the cartesian plane of the image itself, assigning spatial locations to features later on the basis of other data. Digitizing and vectorizing plans and maps resulting from multiple excavations in order to build up a comprehensive archaeological map of a region or site also necessitates not only the use of GIS software but the application of careful data management practices for handling and preserving a collection of digital files that can quickly grow huge.

We'll get insight into just such an effort tomorrow when Tim Shea reports on Duke's "Digital Athens Project".

Let's not forget remote sensing! In RS we use sensors -- devices that gather information in various sections of the electro-magnetic spectrum or that detect change in local physical phenomena. We mount these sensors on platforms that let us take whatever point of view is necessary to achieve the resolution, scale, and scope of interest: satellites, airplanes, drones, balloons, wagons, sleds, boats, human hands. The sensors capture emitted and reflected light in the visible, infrared, and ultraviolet wavelengths or magnetic or electrical fields. They emit and detect the return of laser light, radio frequency energy, microwaves, millimeter waves, and, especially underwater, sound waves. Specialized software is used to analyze and convert such data for various purposes, often into rasterized intensity or distance values that can be visualized by assigning brightness and color scales to the values in the raster grid. Multiple images are often mosaicked together to form continuous images of a landscape or 360 degree seamless panoramas.

Remotely sensed data facilitate the detection and interpretation of landforms, vegetation patterns, and physical change over time, revealing or enhancing understanding of built structures and exploited landscapes, as well as their conservation. This is the sort of work that Sarah Parcak has been popularizing, but it too has decades of practice behind it. In 1990, Tom Sever's dissertation reported on a remote-sensing analysis of the Anasazi road system, revealing a component of the built landscape that was not only invisible on the ground, but that demonstrates that the Anasazi were far more willing than even the Romans to create arrow-straight roads in defiance of topographical impediments. More recently, Prof. Sever and his NASA colleague Daniel Irwin have been using RS data for parts of Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico, to distinguish between vegetation that thrives in alkaline soils and vegetation that doesn't. Because of the Mayan penchant for coating monumental structures with significant quantities of lime plaster, this data has proved remarkably effective in the locating of previously unknown structures beneath forest canopy. The results seem likely to overturn prevailing estimates of the extent of Mayan urbanism, illustrating a landscape far more cleared and built upon than heretofore proposed (cf. Sever 2003).

Given the passion with which I've already spoken about the care and feeding of data, you'll be unsurprised to learn that I'm really looking forward to Nevio Danelon's presentation tomorrow on the capture and curation of remotely sensed data in a digital workflow management system designed to support visualization processes.

I think it's worth noting that both Professor Parcak's recently collaborative work on a possible Viking settlement in Newfoundland, as well as Prof. Sever's dissertation, represent a certain standard in the application of remote sensing to archaeology. RS analysis is tried or adopted for most archaeological survey and excavation undertaken today. The choice of sensors, platforms, and analytical methods will of course vary in response to landscape conditions, expected archaeological remains, and the realities of budget, time, and know-how.

Similarly common, I think, in archaeological projects is the consideration of geophysical, alluvial, and climatic features and changes in the study area. The data supporting such considerations will come from the kinds of sources we've already discussed, and will have to be managed in appropriate ways. But it's in this area -- ancient climate and landscape change -- that I think ancient studies has a major deficit in both procedure and data. Computational, predictive modeling of ancient climate, landscape, and ground cover has made no more than tentative and patchy inroads on the way we think about and map the ancient historical landscape. That's a deficit that needs addressing in an interdisciplinary and more comprehensive way.

I'd be remiss if, before moving on to conclusions, I kept the focus so narrowly on research questions and methods that we miss the opportunity to talk about pedagogy, public engagement, outreach, and cultural heritage preservation. Spatial practice in the humanities is increasingly deeply involved in such areas. The Ancient World Mapping Center's Antiquity a-la Carte website enables users to create and refine custom maps from Pleiades and other data that can then be cited, downloaded, and reused. It facilitates the creation of map tests, student projects, and maps to accompany conference presentations and paper submissions.

Meanwhile, governments, NGOs, and academics alike are brining the full spectrum of spatial methods to bear as they try to prevent damage to cultural heritage sites through assessment, awareness, and intervention. The American Schools of Oriental Research conducts damage assessments and site monitoring with funding in part from the US State Department. The U.S. Committee of the Blue Shield works with academics to prepare geospatial datasets that are offered to the Department of Defense to enhance compliance with the 1954 Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict.

These are critical undertakings as well, and should be considered an integral part of our spatial antiquity practice.

So, how should we gather up the threads of this discussion so we can move on to the more substantive parts of the conference?

I'd like to conclude as I began, by recommending an essay. In this case, I'm thinking of Bethany Nowiskie's recent essay on "capacity and care" in the digital humanities. Bethany is the former director of UVA's Scholars Lab. She now serves as Director of the Digital Library Federation at the Council on Library and Information Resources. I had the great good fortune to hear Bethany deliver a version of this essay as a keynote talk at a project director's meeting hosted by the NEH Office of Digital Humanities in Washington in September of last year. You can find the essay version on her personal website.

Bethany thinks the Humanities must expand its capacity in order not only to survive the 21st century, but to contribute usefully to its grand challenges. To cope with increasing amounts and needs for data of every kind. To move gracefully in analysis and regard from large scales to small ones and to connect analysis at both levels. To address audiences and serve students in an expanding array of modes. To collaborate across disciplines and heal the structurally weakening divisions that exist between faculty and "alternate academics", even as the entire edifice of faculty promotion and tenure threatens to shatter around us.

What is Bethany's prescription? An ethic of care. She defines an ethic of care as "a set of practices", borrowing the following quotation from the political scientist Joan Tronto:

a species of [collective] activity that includes everything we do to maintain, contain, and repair our world, so that we can live in it as well as possible.I think our practice of spatial humanities in ancient studies is just such a collective activity. We don't have to turn around much to know that we are cradled in the arms and buoyed up on the shoulders of a vast cohort, stretching back through time and out across the globe. Creating data and handing it on. Debugging and optimizing algorithms. Critiquing ideas and sharpening analytical tools.

The vast majority of projects on the conference schedule, or that I could think of to mention in my talk, are explicitly and immediately collaborative.

And we can look around this room and see like-minded colleagues galore. Mentors. Helpers. Friends. Comforters. Makers. Guardians.

And we have been building the community infrastructure we need to carry on caring about each other and about the work we do to explain the human past to the human present and to preserve that understanding for the human future. We have centers and conferences and special interest groups and training sessions. We involve undergraduates in research and work with interested people from outside the academy. We have increasingly useful datasets and increasingly interconnected information systems. Will all these things persist? No, but we get to play a big role in deciding what and when and why.

So if there's a stable orbit to be found, I think it's in continuing to work together and to do so mindfully, acknowledging our debts to each other and repaying them in kind.

I'm reminded of a conversation I had with Scott Madry, back in the early aughts when we were just getting the Mapping Center rolling and Pleiades was just an idea. As many of you know, Scott together with Carole Crumley and numerous other collaborators here at UNC and beyond, have been running a multidimensional research project in Burgundy since the 1970s. At one time or another the Burgundy Historical Landscapes project has conducted most of the kinds of studies I've mentioned tonight, all the while husbanding a vast and growing store of spatial and other data across a daunting array of systems and formats.

I think that the conversation I'm remembering with Scott took place after he'd spent a couple of hours teaching undergraduate students in my seminar on Roman roads and land travel how to do orthophoto analysis the old fashioned way: with stereo prints and stereoscopes. He was having them do the Sarah Parcak thing: looking for crop marks and other indications of potentially buried physical culture. After the students had gone, Scott and I were commiserating about the challenges of maintaining and funding long-running research projects. I was sympathetic, but know now that I really didn't understand those challenges then. Scott did, and I remember what he said. He said: "We were standing on that hill in Burgundy twenty years ago, and as we looked around I said to Carol: 'somehow, we are going to figure out what happened here, no matter how long it takes.'"

That's what I'm talking about.

Labels:

ancgeo,

awmc,

awmc2016,

batlas,

collaboration,

conferences,

cultural heritage protection,

dh,

digclass,

epidoc,

hgis,

neogeography,

nlp,

pelagios,

perseus,

pleiades,

rants,

tei

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)